Incendies Reviews

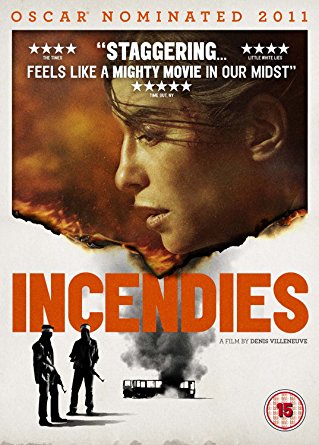

This was the official website for the 2010 film, INCENDIES, director Denis Villeneuve's gripping, era-jumping drama about a family melded to its war-torn past. Content is from the site's archived pages and other outside review sources.

Incendies Official Trailer 2010

FILM DESCRIPTION: Director Denis Villeneuve adapts Wajdi Mouawad's play concerning a pair of twins who make a life-altering discovery following the death of their mother. Upon learning that their absentee father is still very much alive and they also have a brother they have never met, the pair travels to the Middle East on a mission to uncover the truth about their mystery-shrouded past.

Rating: R (for some strong violence and language)

Genre: Drama

Directed By: Denis Villeneuve

In Theaters: Apr 22, 2011 Limited

On Disc/Streaming: Sep 13, 2011

RottenTomatometer CRITICS 93% | AUDIENCE 92%

REVIEWS

Scavenger Hunt for Family Secrets Across Time and Geography

By A. O. SCOTTAPRIL 21, 2011

By A. O. SCOTTAPRIL 21, 2011

Denis Villeneuve’s “Incendies,” a film very much occupied with some of the grisly realities of recent history, nonetheless has the structure, and some of the atmosphere, of an ancient folk tale. It is a quest narrative, about children searching out the mysteries of their parentage, and also the story of a resourceful heroine, the mother of those children, surviving an almost unimaginable series of ordeals.

These entwined plots unfurl in the recognizable, modern world — in Quebec and an unnamed country that closely resembles Lebanon — and at the same time in an allegorical universe governed by the tightly coiled logic of fate. Judged by strictly naturalistic standards, the flurry of revelations and coincidences that wrap up the double story may seem implausible. But strict verisimilitude would not serve the dramatic ends that “Incendies,” based on a play of the same name by Wajdi Mouawad, sets out to serve. The knotted destinies of its characters are like the family secrets in a Shakespearean or classical comedy but turned to a darker purpose.

Among the film’s subjects is kinship, the often painful ways that bonds of blood connect strangers and enemies. When their mother, Nawal (Lubna Azabal), dies, Jeanne and Simon Marwan (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin and Maxim Gaudette), twins who have grown up Canadian, discover that her last will and testament requires them to set off on a kind of scavenger hunt across time and geography. Jeanne, who is pursuing a graduate degree in mathematics, is charged with finding the father she and Simon never knew. Simon, who seems more deeply scarred by the obscure tragedy of their mother’s solitary, circumspect life, is instructed to seek out another brother, whose existence he and his sister never suspected.

The twins are encouraged and assisted in their quest by Jean Lebel (Rémy Girard) the avuncular notary who had been their mother’s employer for many years. Their travels in a relatively peaceful and functional 21st-century quasi-Lebanon are interwoven with episodes from their mother’s life during the nation’s long and gruesome civil war. Those chapters, shifting from hillside villages to cities and refugee camps, from the verdant north of the country to its dusty south, give Mr. Villeneuve’s film novelistic depth and epic expansiveness. They also display his sensitive eye for landscape (the non-Canadian sections were shot in Jordan) and his discreet use of digital effects to simulate the large-scale effects of war. The revelations of culture and societal norms are a strikingly provocative aspect of this film that warrants consideration on its own.

Though its details are fictional, this chronicle is impressively nuanced in its rendering of Lebanese politics and society in the 1970s and ’80s. As a young woman, Nawal provokes the violent disapproval of her family when she falls love with a Muslim and flees her hometown for the capital. Subsequently, as a student and an activist, a clandestine militant and a political prisoner, she crosses back and forth between the warring groups. In one of the most wrenching scenes the Christian identity she had repudiated saves her life but at the price of making her the helpless witness and silent accomplice to a massacre by Phalangist fighters.

Mr. Villeneuve tells Nawal’s story in a way that is both subtle and emphatic, and Ms. Azabal, portraying Nawal from hopeful youth to despairing middle age, gives a performance that is all the more powerful for the restrained, unshakeable sense of dignity she brings to it. The depth and complexity of her anger is both a product and a mirror of her native country’s self-destructive pathology, and as the full horror of her life is disclosed, she becomes, in her children’s eyes and the audience’s, as grand and tragic as the heroine of an opera.

But if “Incendies” were her story alone, it might have been too much: an overwrought and awkward slog through a bloody stretch of the past. The perspective of Jeanne and Simon, modern Canadians wholly unaware of their roots in that history, makes the film into something more elusive and complex, a meditation on memory and identity that recalls some of the recent films of Atom Egoyan. How are the twins to understand their relationship with their mother in the light of what they learn about her? What does it mean for them to be so intimately and yet obscurely tied to an inheritance of rape, torture, assassination and terror? What could help them understand this legacy and move beyond it?

+++

May 26, 2011 | Rating: A-

Chris Vognar Dallas Morning News / Top Critic

Rage has no expiration date in Incendies, director Denis Villeneuve's gripping, era-jumping drama about a family melded to its war-torn past.

+++

June 22, 2011 | Rating: 3/5

David Jenkins / Time Out / Top Critic

Pain, suffering, humiliation, bloodshed, martyrdom, misogyny, corruption, political instability, family secrets and death: the Oscar-nominated ‘Incendies’ by Québécois director Denis Villeneuve, based on a play by Wajdi Mouawad, is not what you’d call a laugh riot. A smouldering exploration of family ties and how the hardships of the recently deceased can have a damaging psychological effect on those left behind, it’s framed as a hokey mystery, set up via a cryptic last will and testament left by a mother (Lubna Azabal) to her son (Maxim Gaudette) and daughter (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin). She insists her kids travel from Montreal to the Middle East and uncover the identities of an estranged brother and father. That she wasn’t able to muster the strength to disclose these details during her lifetime offers an eloquent window on her past agonies.

Having created a film reminiscent of the sand-blasted misery workouts of Alejandro González Iñárritu (specifically ‘Babel’), Villeneuve appears to believe that narrative contrivance can and should be overlooked if the emotional pay-off is hefty enough. In fact, where there should be tears there’s a void simply because events become more far-fetched the further this twisty tale unfurls. The less said about what the kids find on their journey the better, because, as tough as the story is to swallow, Villeneuve at least builds his film with a measure of understated style. But while the characters lack credibility, the social backdrop and texture of the performances certainly don’t, and Villeneuve manages to say more about the sorry state of the Middle East (Lebanon is suggested but never mentioned) through the bold, crisp way he shoots faces, buildings and parched, beige-brown landscapes. So let’s call it’s a strong film based on a weak story.

+++

The Guardian

Jun 25, 2011

From its arresting opening to its shattering conclusion, the Canadian film Incendies is muscular, emotional film-making of the highest order, self-confident in its delivery yet always respectful of its characters' plight. It starts in slo-mo, to the sound of Radiohead, in what looks like a children's Qu'ran school, in a desert, where we see boys having their heads shaved by soldiers. One of the boys fixes the camera with a chilling stare as hair falls around his feet.

The film then switches to a law firm in Montreal, where a mother's will is being read to her grief-stricken twins, daughter Jeanne (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and son Simon (Maxim Gaudette). The lawyer Maître Lebel is played by the great Quebecois actor Rémy Girard, from another Canadian family saga, Denys Arcand's Les Invasions Barbares. This, too, is a tale of family, identity and, perhaps, forgiveness as the will sets Jeanne, a student of pure maths, off on a quest to discover what happened in her mother Nawal's past as she was growing up in the Middle East.

The film cuts from Nawal's (Belgium-born actress Lubna Azabal) turbulent past back to Melissa as she, listening to Radiohead on her iPod, sifts the war-ravaged ruins of this unspecified country in the present.

Director Denis Villeneuve, adapting a stage play by Wajdi Mouawad, daubs chapter headings in a bold red font across the screen, helpful signposts as we plunge deeper into this mystery, yet one always has the sense the film knows exactly where it's headed.

Even as it deals with the tangled knots left by conflict, Villeneuve never seems deceptive with his storytelling. "War has a merciless logic," a former warlord tells Melissa, and this story powers to a climax some might find contrived but which left me reeling, as if whacked over the head with a hardback copy of a Dickens novel.

+++

Review: 'Incendies' A Strong Film Ultimately Held Back By A Nauseating Final Plot Twist

Christopher Bell

Apr 21, 2011

Oh egregious plot twists, when will you stop ruining our movies? You’ve already turned us against M. Night Shyamalan (though we can’t blame you for his last three disasters) and consistently do everything you can to obliterate affection for anything that precedes you. Well, we’re not going to let you win this time, because Denis Villeneuve’s 2011 Foreign Oscar contender “Incendies” was completely competent before you reared your despicable head. Maybe it’s not very profound, but there’s good work here. You’ll get yours in a little bit.

In a very striking opening, young Arab boys are rounded up somewhere in the Middle East (it’s unspecified, but the plot and locale have much in common with Lebanon), waiting their turn for an extreme buzz cut. The camera looms and presses in using slow dolly movements, giving a foreboding and uncomfortable tone to a rather no-nonsense physical scene. For better or worse, Radiohead’s “You and Whose Army” sinks in, our focus leaves the unsettling opener and introduces each character separately before finally taking us to a dreary office to jump start the plot.

Notary Jean Libel (Remy Girard, “The Barbarian Invasions“) somberly executes the will of his former secretary Nawal (Lubna Azabal, “Paradise Now“) to her teenage children, twins Simon (Maxim Gaudette) and Jeanne (Melissa Desormeaux-Poulin), who are charged with the task of finding their long-lost father and brother and giving them each a handwritten letter composed by the woman before her death. So aside from being completely broken over the passing of their only parent, they are also staggered to discover that their father is alive and that they have a brother — never mind the bizarre assignment that’s presented to them. Talk about devastating pressure. While Simon would rather just bury her and be done with it, Jeanne respects her mother’s wishes and begins the quest, leaving Canada for the Middle East. As she moves from location to location playing detective, she discovers the many different, severe incidents that shaped her parent — and we too are treated to these past-sequences, following Nawal as she goes from top mathematician to hired killer, from prisoner to child-bearer.

Nawal’s story opens with the murder of her first love, the man who impregnated her out of wedlock, and is forced to pay for the shame brought to her family. She is spared by her grandmother, who then sends both her and the baby away — Nawal to distant relatives, the baby to an orphanage. Rising above the trauma, she begins her studies promisingly, but it seems like trouble is too fond of her — yet again she finds herself in a mess, caught in the middle of a war and forced to go on the run. This coupled with the latter-day storyline certainly sounds like a lot, but even with a two hour and ten minute runtime, the film couldn’t feel any quicker. It’s not the puzzle that’s the driving force, it’s Azabal, who carries her portion with such commanding strength that it’s a wonder she doesn’t have more opportunities to take the lead. Similarly, things are subdued in the children’s plot, but Mom’s is where all the action is — from bus burnings to sniping children, there’s not a slight moment to be found. The visuals don’t skimp here and this section holds some dazzlingly beautiful shots and set design, a stark contrast to the present timeline’s more quiet, lifeless scenes. Admittedly, these segments contain some of the more extreme elements- – and really, they’re going to get attention no matter what — but they are executed brilliantly regardless of their flagrance. In fact, it’s a bit disappointing that none of these long stretches (which are so separated they feel like vignettes) make up the entire meat of the movie; surely one of them could’ve been expanded and made into something truly powerful. The aforementioned scene involving children navigating through rubble and blown up roads while simultaneously avoiding a hidden gunner’s cross-hairs is difficult to forget — but the filmmaker’s too fond of his other characters, cutting back to the protagonist’s kin and losing potency along the way.

There’s also that damn plot twist — which is, obviously, the answer as to who their father and brother actually are. No spoilers, but the result is so overly-shocking that the real surprise is the audacity of the filmmaker to commit to such a thing — to reference an early capsule review of ours, it’s more or less lifted from a soap opera. Contained within the story is a loose examination of human beings and their different facets (such as the mother being a killer, prisoner, student, refugee, etc.) which the revelation backs up a bit more, but the general idea isn’t presented with enough insight for it to be totally forgivable. Also a problem is the undefined location: while it’s fully realized with its own decades-fueled religious battles and harrowing war-time conditions, Villeneuve’s reluctance to label it as any real-world country makes things hard to follow and too vague. In interviews he plays down the connection to Lebanese history, hoping for it to be universal and neutral — the latter is bullshit (you have scenes with a child being shot by a sniper and it’s not critical of anything?) but the impersonal, watery nature of the former is what really holds things back, and it’s unlikely to elicit anything further than a shrug.

Though it is (mostly) a story well told, shocking coincidences are stringed together and depth is overlooked. When the case is finally cracked and the near appalling information is unveiled, the film deflates. Villeneuve proves with “Incendies” that he can successfully take audiences on an engaging ride, but one drastic final move and lack of anything to say only leaves a bitter taste in the mouth as opposed to anything memorable. We’ll ride with you again, but next time try keeping the last act twists to a minimum. [B-]

+++

Reasons Why “Incendies” Is Denis Villeneuve’s Overlooked Masterpiece

03 DECEMBER 2017

BY HRVOJE GALIĆ

The Woman Who Sings

While being imprisoned, Nawal shows her defiance toward violence by the act of continuous singing; she is remembered as the Woman Who Sings by others, and this act of will is what defines her, the refusal to be broken in the face of horrors. The former prison guard says: “They did everything to break her. In the end she still stood tall and looked them in the eye. They’d never seen anyone like her. She wouldn’t break. They were enraged.”

In a memorable scene, she is shown singing while we hear screams in the adjacent room. Nawal is stunningly played by Lubna Azabal; her anger and deep sense of commitment are of key importance to the film’s narrative and are centered around the figure of a woman who stands tall in the midst of the horrors of war and humiliation.

Working for the student newspapers, she tried to promote peace, but after witnessing the increasing number of deaths among refugees and while remembering her child’s father, she gives in to violence, as she says, showing her enemies what life has taught her. The brutality of life she experiences is a motive for her to start the chain of events that led to others with “merciless” logic, as one character in the film says.

When she is on the bus where Muslims are killed, and she is not since she is a Christian, she partakes in an act of violence in a way, since she identifies with the murderers. The chain of anger that is seen on the face of her young son still needs to be broken.

Multilayered narrative

The film is divided into chapters, each dealing with a particular person crucial to the narrative or the place where it occurs. Thus, the places are constitutive to the people inhabiting them; it is a also journey through time, from one generation to the next. Different layers are juxtaposed or lead to others, building an intricate narrative which, while moving through different times and places, forms a structure steadily moving toward its horrendous conclusion.

Spanning more than 30 years, the movie covers a period of war and violence and the consequences of that violence on a family now living in another part of the world. While grandiose in scope, it is humble in its narrative devices. There are no great action scenes to remember; instead we witness a tide of emotions that builds in a multifaceted manner. The twins’ mother’s will is a starting point from which the events unfold.

From the reluctance to accept the truth, to the search for one’s heritage and ultimately to its acceptance, the film cuts from one time and place to another in a nonlinear pattern. Villeneuve sees to it that the people in focus are portrayed in a manner which shows all the complex layers of their character and the context from which their suffering emerges. The film is multi-layered not only because of its structure, but also because it shows a wide range of emotions and psychological reactions to extreme life situations.

Violence and forgiveness

Although Villeneuve said the main theme of the film is not war, and it is certainly more of a context than a theme, one cannot escape the notion that the very context of war and violence is of central importance regarding the fates of the characters, the deconstruction of their identity and its latter re-appropriation.

When it comes to Nawal, she is surrounded by violence and deeply suffers its consequences, and that suffering is later transferred to her children. In the face of an apparent never-ending circle of violence and pain, Villeneuve offers a chance of forgiveness and of being together after the harm has been inflicted.

At the end of the movie, Nawal writes in her letter: “Take solace. For nothing means more than being together. You were born of love. So your brother and sister were born of love too. Nothing means more than being together.”

The message of Villeneuve’s movie is that in spite of the fact that violence can be horrendous and great damages can be inflicted, there is always a possibility for forgiveness, starting over, and most importantly, starting a new life in communion. This can be understood in the context of interpersonal relationships, but can also be applied to ethnic and religious groups that need to find a way to live peacefully in coexistence.

Tragedy and catharsis

In Greek tragedies, the events are preordained by what we call “fate,” and the actions of the characters may necessarily lead to the tragic ending. The most famous play in which the characters are unaware of each other’s identity is “Oedipus Rex,” and “Incendies” can be regarded similar to it in this respect. Nevertheless, the ignorance at some point turns into recognition without which there would be no tragedy. The twins’ recognition of their identity leads to their awareness of tragic events befalling them and is in itself tragic.

In Aeschylus’ tragedy “The Eumenides,” Orestes, after killing his mother Clytemnestra, is tormented by the Furies who refuse to leave him at peace. On the other hand, the perpetrator in “Incendies” is asked by the victim to take solace, and tells him she loves him. The message is that the circle of violence and suffering can come to an end.

Aristotle defined catharsis as the purification of emotions through art, such as pity and fear. After they find out the terrible truth, the twins go swimming. The pool is often shown throughout the film; it is a place where the first recognition is taking place. This is symbolic, since water is associated with purification. We cannot help but feel pity for the characters, who are caught in a circle of suffering and trauma. This leads to catharsis experienced by the viewer and the characters alike.

PRESS

'Incendies' Takes Top Prize at Canadian Film Awards

3/10/2011 by Etan Vlessing

TORONTO -- Denis Villeneuve’s Incendies took home top honors at the Genies, Canada’s film awards, on Thursday night. The Quebec drama about a mother who hides tragic secrets that her two children must uncover in the Middle East earned best motion picture, the top directors’ prize and best adapted screenplay for Villeneuve.

Sony Pictures Classics will release the film stateside April 22, beginning with engagements in New York and Los Angeles.

+++

OSCARS 2011 | “Incendies” Director Denis Villeneuve

OSCARS 2011 | "Incendies" Director Denis Villeneuve

Brian Brooks

Feb 15, 2011

This interview with “Incendies” director Denis Villeneuve was originally published during indieWIRE’s coverage of the 2010 Toronto International Film Festival. The Canadian film has since gone on to garner a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at this year’s Academy Awards.

Quebec director Denis Villeneuve received a standing ovation from a clearly stunned audience following the premiere screening of “Incendies” on Monday evening in Toronto. Last week it received raves during its sneak in Telluride and the film received praise and a standing ovation in Venice. Certainly not light viewing, the film – broken into chapters – slowly reveals one striking twist after another.

“I was able to convince the author to let me do the movie and he told me it’s going to take you a lot of time and you’re going to suffer and I’m going back to Paris and I cannot help you,” writer/director Denis Villeneuve told Eugene Hernandez during the indieWIRE chat series this week at the TIFF Filmmaker Lounge.

Based on the play, Scorched by Wajdi Mouawad, the heart-wrenching story unfolds amidst the brutality of civil war in Lebanon. During the reading of their mother’s will in Montreal, twins Simon (Maxim Gau) and Jeanne (Melissa Desormeaux-Poulin) learn for the first time that they have a brother and that their father – whom they believed was dead – is alive. The pair is troubled when their mother’s notary reveals that it is their mother’s request to deliver envelopes to their long-lost brother and father. Simon is angry and hesitant to fulfill her wishes, but Jeanne sets off to the Middle East to search for her relatives.

Eventually joined by Simon, the pair learn the harsh realities and dark secrets from their mother’s life. Every arrival to a new village unveils a secret and the 130 minute feature, spoken mostly in French and Arabic with English subtitles, flashes back to their mother’s (Lubna Azabal) traumatic ordeal leading up to their birth and emigration to Canada.

Commenting on the film in Venice for indieWIRE, Shane Danielsen called “Incendies” a “coup-de-theatre” and praised the director’s current film and past work.

“Villeneuve is a phenomenally gifted writer and director, as anyone who saw ‘August 32nd on Earth’ or ‘Polytechnique’ will attest; and this film stands as the summation of his achievements to date. The standing ovation he received at its public premiere was entirely deserved.”

“It’s a beautiful and powerful story that I relate to a Greek tragedy,” Villeneuve noted in Toronto. “It’s a modern story with a sort of Greek tragedy element in it.”

Villeneuve said that he wasn’t familiar with Arab culture prior to taking on “Incendies,” but noted that observation was key to filmmaking and learning about culture.

“I think a good director is a good listener. I don’t know anything about war [and] I didn’t know a lot about Arabic people. So in order for me to adapt the screenplay, I had to be a listener… You have to put ego aside, which is difficult for a filmmaker. Half the movie I re-wrote while talking to actors there. And the challenge for me was to be faithful to Arabic culture, but I think we succeeded.”

American audiences will have the chance to judge for themselves. Villeneuve announced that the film had been picked up during a post-screening Q&A Monday evening. Sony Pictures Classics will release the film in the U.S.